Organization was essential. As was the ability to maintain flow in the presentation of my case. how to do it all?

I turned to a tool that I have long been a big believer in: Mind mapping. My preferred mind mapping software? Mind Jet.

For a comprehensive explanation I turn to the good folks at Wikipedia:

Mind map

A mind map is a diagram used to represent words, ideas, tasks, or other items linked to and arranged around a central key word or idea. Mind maps are used to generate, visualize, structure, and classify ideas, and as an aid to studying and organizing information, solving problems, making decisions, and writing.

The elements of a given mind map are arranged intuitively according to the importance of the concepts, and are classified into groupings, branches, or areas, with the goal of representing semantic or other connections between portions of information. Mind maps may also aid recall of existing memories.

By presenting ideas in a radial, graphical, non-linear manner, mind maps encourage a brainstorming approach to planning and organizational tasks. Though the branches of a mindmap represent hierarchical tree structures, their radial arrangement disrupts the prioritizing of concepts typically associated with hierarchies presented with more linear visual cues. This orientation towards brainstorming encourages users to enumerate and connect concepts without a tendency to begin within a particular conceptual framework.

The mind map can be contrasted with the similar idea of concept mapping. The former is based on radial hierarchies and tree structures denoting relationships with a central governing concept, whereas concept maps are based on connections between concepts in more diverse patterns.

Contents |

Characteristics

Mind maps are, by definition, a graphical method of taking notes. Their visual basis helps one to distinguish words or ideas, often with colors and symbols. They generally take a hierarchical or tree branch format, with ideas branching into their subsections. Mind maps allow for greater creativity when recording ideas and information, as well as allowing the note-taker to associate words with visual representations. Mind maps differ from concept maps in that mind maps focus on only one word or idea, whereas concept maps connect multiple words or ideas.

A key distinction between mind maps and modelling graphs is that there is no rigorous right or wrong with mind maps, relying on the arbitrariness of mnemonic systems. A UML Diagram or a Semantic network has structured elements modelling relationships, with lines connecting objects to indicate relationship. This is generally done in black and white with a clear and agreed iconography. Mind maps serve a different purpose: they help with memory and organisation. Mind maps are collections of words structured by the mental context of the author with visual mnemonics,and, through the use of colour, icons and visual links are informal and necessary to the proper functioning of the mind map.

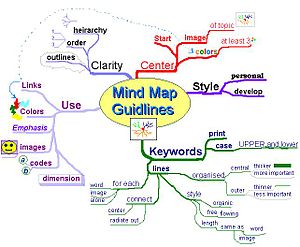

Mind map guidelines

In his books on Mind Maps author Tony Buzan suggests using the following guidelines for creating Mind Maps:

- Start in the center with an image of the topic, using at least 3 colors.

- Use images, symbols, codes, and dimensions throughout your Mind Map.

- Select key words and print using upper or lower case letters.

- Each word/image is best alone and sitting on its own line.

- The lines should be connected, starting from the central image. The central lines are thicker, organic and flowing, becoming thinner as they radiate out from the centre.

- Make the lines the same length as the word/image they support.

- Use multiple colors throughout the Mind Map, for visual stimulation and also to encode or group.

- Develop your own personal style of Mind Mapping.

- Use emphasis and show associations in your Mind Map.

- Keep the Mind Map clear by using radial hierarchy, numerical order or outlines to embrace your branches.

This list is itself more concise than a prose version of the same information and the Mind Map of these guidelines is itself intended to be more memorable and quicker to scan than either the prose or the list.

History

Pictorial methods for recording knowledge and modelling systems have been used for centuries in learning, brainstorming, memory, visual thinking, and problem solving by educators, engineers, psychologists, and others. Some of the earliest examples of such graphical records were developed by Porphyry of Tyros, a noted thinker of the 3rd century, as he graphically visualized the concept categories of Aristotle. Philosopher Ramon Llull (1235–1315) also used such techniques.

The semantic network was developed in the late 1950s as a theory to understand human learning and developed further by Allan M. Collins and M. Ross Quillian during the early 1960s.

British popular psychology author Tony Buzan claims to have invented modern mind mapping.[1] He claimed the idea was inspired by Alfred Korzybski's general semantics as popularized in science fiction novels, such as those of Robert A. Heinlein and A.E. van Vogt. Buzan argues that while "traditional" outlines force readers to scan left to right and top to bottom, readers actually tend to scan the entire page in a non-linear fashion. Buzan also uses popular assumptions about the cerebral hemispheres in order to promote the exclusive use of mind mapping over other forms of note making.

The mind map continues to be used in various forms, and for various applications including learning and education (where it is often taught as "webs", "mind webs", or "webbing"), planning, and in engineering diagramming.

When compared with the concept map (which was developed by learning experts in the 1970s) the structure of a mind map is a similar radial, but is simplified by having one central key word.

Uses

A mind map is often created around a single word or text, placed in the center, to which associated ideas, words and concepts are added.

Mind maps have many applications in personal, family, educational, and business situations, including notetaking, brainstorming (wherein ideas are inserted into the map radially around the center node, without the implicit prioritization that comes from hierarchy or sequential arrangements, and wherein grouping and organizing is reserved for later stages), summarizing, revising, and general clarifying of thoughts. One could listen to a lecture, for example, and take down notes using mind maps for the most important points or keywords. One can also use mind maps as a mnemonic technique or to sort out a complicated idea. Mind maps are also promoted as a way to collaborate in color pen creativity sessions.

Mind maps can be used for:

- problem solving

- outline/framework design

- anonymous collaboration

- marriage of words and visuals

- individual expression of creativity

- condensing material into a concise and memorable format

- team building or synergy creating activity

- enhancing work morale

Despite these direct use cases, data retrieved from mind maps can be used to enhance several other applications, for instance expert search systems, search engines and search and tag query recommender[2]. To do so, mind maps can be analysed with classic methods of information retrieval to classify a mind map's author or documents that are linked from within the mind map[2].

Mindmaps can be drawn by hand, either as "rough notes" during a lecture or meeting, for example, or can be more sophisticated in quality. An example of a rough mind map is illustrated. There are also a number of software packages available for producing mind maps.

Effectiveness in learning

Buzan[3] claims that the mind map is a vastly superior note taking method because it does not lead to a "semi-hypnotic trance" state induced by other note forms. Buzan also argues that the mind map uses the full range of left and right human cortical skills, balances the brain, taps into the alleged "99% of your unused mental potential", as well as intuition (which he calls "superlogic"). However, scholarly research suggests that such claims may actually be marketing hype based on misconceptions about the brain and the cerebral hemispheres. Critics argue that hemispheric specialization theory has been identified as pseudoscientific when applied to mind mapping.[4]

Farrand, Hussain, and Hennessy (2002) found that spider diagrams (similar to concept maps) had a limited but significant impact on memory recall in undergraduate students (a 10% increase over baseline for a 600-word text only) as compared to preferred study methods (a 6% increase over baseline). This improvement was only robust after a week for those in the diagram group and there was a significant decrease in motivation compared to the subjects' preferred methods of note taking. Farrand et al. suggested that learners preferred to use other methods because using a mind map was an unfamiliar technique, and its status as a "memory enhancing" technique engendered reluctance to apply it. Nevertheless the conclusion of the study was "Mind maps provide an effective study technique when applied to written material. However before mind maps are generally adopted as a study technique, consideration has to be given towards ways of improving motivation amongst users."[5]

Pressley, VanEtten, Yokoi, Freebern, and VanMeter (1998) found that learners tended to learn far better by focusing on the content of learning material rather than worrying over any one particular form of note taking.[6]

Tools

Mind mapping software can be used effectively to organize large amounts of information, combining spatial organization, dynamic hierarchical structuring and node folding. Software packages can extend the concept of mind mapping by allowing individuals to map more than thoughts and ideas with information on their computers and the internet, like spreadsheets, documents, internet sites and images.

Trademarks

Psychologist Edward Tolman is credited with the creation of cognitive mapping.[7] The use of the term "Mind Maps" is claimed as a trademark by The Buzan Organisation, Ltd. in the United Kingdom[8] and the United States.[9] The trademark does not appear in the records of the Canadian Intellectual Property Office.[10] In the US "Mind Maps" is trademarked as a "service mark" expressly for "EDUCATIONAL SERVICES, NAMELY, CONDUCTING COURSES IN SELF-IMPROVEMENT" — other products and services are not covered by the trademark.

See also

References

- ^ Buzan claims mind mapping his invention in interview. KnowledgeBoard retrieved Jan. 2010.

- ^ a b Beel, Jöran; Gipp, Bela; Stiller, Jan-Olaf (2009). "Information Retrieval On Mind Maps - What Could It Be Good For?". Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Collaborative Computing: Networking, Applications and Worksharing (CollaborateCom'09). Washington: IEEE. http://www.sciplore.org/publications_en.php

- ^ Buzan, Tony. (2000). The Mind Map Book, Penguin Books, 1996. ISBN 978-0452273221

- ^ Williams (2000) Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience. Facts on file. ISBN 978-0816033515

- ^ Farrand, P.; Hussain, F.; Hennessy, E. (2002). "The efficacy of the mind map study technique". Medical Education 36 (5): 426–431. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01205.x. PMID 12028392. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118952400/abstract. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ^ Pressley, M., VanEtten, S., Yokoi, L., Freebern, G., & VanMeter, P. (1998). "The metacognition of college studentship: A grounded theory approach". In: D.J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, & A.C. Graesser (Eds.), Metacognition in Theory and Practice (pp. 347-367). Mahwah NJ: Erlbaum ISBN 9780805824810

- ^ Tolman E.C. (July 1948). "Cognitive maps in rats and men". Psychological Review 55 (4): 189–208. doi:10.1037/h0061626. PMID 18870876.

- ^ Trade Mark 1424476, UK Intellectual Property Office, filed Nov. 1990

- ^ US Trademark, USPTO Trademark Application and Registration Retrieval system

- ^ Canadian Intellectual Property Office

Please visit hardinglaw.com for more information of Harding & Associates Family Law

No comments:

Post a Comment